This week at the SFC: The White Diamond

Thursday 30 March, 2006

THE WHITE DIAMOND (Werner Herzog/ 2005/ 90’)

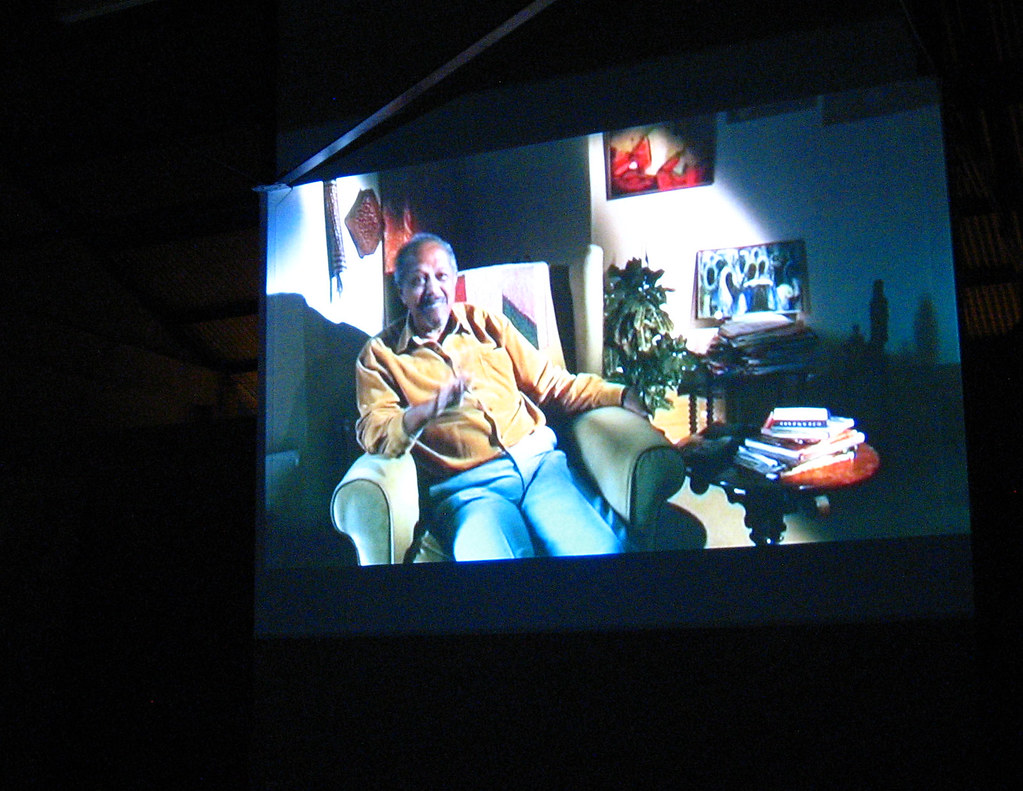

Werner Herzog's film The White Diamond, a documentary, was filmed in the lush jungle of Guyana.

In this documentary, the forest looms as a haunting presence, a backdrop appropriate to the story of loss, tragedy and eventual victory.

The story that Herzog has focused on is the work of a mildly eccentric British aeronautic engineer, Graham Dorrington, who has invented an airship that resurrects the design of early 20th-century zeppelins on a smaller scale to create a craft capable of hovering at the level of the jungle canopy at slow speeds and in relative silence.

His objectives for the creation are to allow deeper research into the diverse flora of the forest canopy, a potential biotechnology goldmine. On watching Dorrington's wide-eyed, breathless presentations of his aircraft, however, one develops the sneaking sense that he is primarily interested in aviation in its own right.

The haunting image of a balloon floating over the jungle is an appropriate metaphor for Werner Herzog's meditative new film The White Diamond.

That ambition is clearly a source of immense motivation for Dorrington, yet it is also the reason for his deep sadness, as a similar design of the craft shown in the film had been used 10 years earlier in Sumatra and resulted in the tragic death of his friend, Dieter Plage.

The German cinematographer fell to his death in what was an unavoidable accident unrelated to any design flaw on Dorrington's part. Nevertheless, the professor bears his sorrow over the death quite openly. The experiments with the new craft, it seems, are an attempt to surmount that pain and loss and, perhaps, bring some meaning to Plage's death.

On site in Guyana, Herzog stumbles upon a parallel story of loss and longing in the character of local Rastafarian Mark Anthony, a diamond miner who is a hired hand in the professor's project. Anthony quietly and placidly reveals to Herzog the story of the loss of his family -- eight brothers, two sisters and his mother -- who have all emigrated to Spain and who he wishes to see more than anything else.

As Anthony watches the professor undertake test flights of the craft, he muses how he would like to fly the craft over the Atlantic Ocean and land on his family's roof in Malaga, Spain, and say to them, "Hello, I am home." Ultimately, there are two heroes in the film, Dorrington and Anthony. Dorrington overcomes his ghosts and past failures by fine-tuning his craft and successfully flying it around the jungle canopy with Herzog, who comes along for the ride to film.

Anthony, meanwhile, presents a figure of strength and perseverance, as well as deep wisdom. At one point, when Herzog poses an unusually banal question to him, Anthony flatly replies, "I cannot hear you for the thunder that you are," effectively brushing off the director. He is clearly deeply appreciated by the crew for his composure and his optimism in the face of hardship. Finally, he's offered a ride, after which he comments that his only regret was that his pet rooster wasn't able to join him.

As in Aguirre, the jungle offers up some spectacular images that, when accompanied by the eerie soundtrack, compound a sense of mystery and foreboding. The tone raises the suspense of the film, as we are gradually told of the details of Plage's death and begin to fear a possible repeat of the tragedy with the new craft.

Dorrington's apparent casual attitude toward procedure and safety provides ample reason to suspect that such could be the project's eventual conclusion.

But the enduring allure of flight, symbolized by the film's images of the forest's swift birds, and the strength of ambition fused with ingenuity and hope see the project through to its spectacular ending.

THE WHITE DIAMOND (Werner Herzog/ 2005/ 90’)

Werner Herzog's film The White Diamond, a documentary, was filmed in the lush jungle of Guyana.

In this documentary, the forest looms as a haunting presence, a backdrop appropriate to the story of loss, tragedy and eventual victory.

The story that Herzog has focused on is the work of a mildly eccentric British aeronautic engineer, Graham Dorrington, who has invented an airship that resurrects the design of early 20th-century zeppelins on a smaller scale to create a craft capable of hovering at the level of the jungle canopy at slow speeds and in relative silence.

His objectives for the creation are to allow deeper research into the diverse flora of the forest canopy, a potential biotechnology goldmine. On watching Dorrington's wide-eyed, breathless presentations of his aircraft, however, one develops the sneaking sense that he is primarily interested in aviation in its own right.

The haunting image of a balloon floating over the jungle is an appropriate metaphor for Werner Herzog's meditative new film The White Diamond.

That ambition is clearly a source of immense motivation for Dorrington, yet it is also the reason for his deep sadness, as a similar design of the craft shown in the film had been used 10 years earlier in Sumatra and resulted in the tragic death of his friend, Dieter Plage.

The German cinematographer fell to his death in what was an unavoidable accident unrelated to any design flaw on Dorrington's part. Nevertheless, the professor bears his sorrow over the death quite openly. The experiments with the new craft, it seems, are an attempt to surmount that pain and loss and, perhaps, bring some meaning to Plage's death.

On site in Guyana, Herzog stumbles upon a parallel story of loss and longing in the character of local Rastafarian Mark Anthony, a diamond miner who is a hired hand in the professor's project. Anthony quietly and placidly reveals to Herzog the story of the loss of his family -- eight brothers, two sisters and his mother -- who have all emigrated to Spain and who he wishes to see more than anything else.

As Anthony watches the professor undertake test flights of the craft, he muses how he would like to fly the craft over the Atlantic Ocean and land on his family's roof in Malaga, Spain, and say to them, "Hello, I am home." Ultimately, there are two heroes in the film, Dorrington and Anthony. Dorrington overcomes his ghosts and past failures by fine-tuning his craft and successfully flying it around the jungle canopy with Herzog, who comes along for the ride to film.

Anthony, meanwhile, presents a figure of strength and perseverance, as well as deep wisdom. At one point, when Herzog poses an unusually banal question to him, Anthony flatly replies, "I cannot hear you for the thunder that you are," effectively brushing off the director. He is clearly deeply appreciated by the crew for his composure and his optimism in the face of hardship. Finally, he's offered a ride, after which he comments that his only regret was that his pet rooster wasn't able to join him.

As in Aguirre, the jungle offers up some spectacular images that, when accompanied by the eerie soundtrack, compound a sense of mystery and foreboding. The tone raises the suspense of the film, as we are gradually told of the details of Plage's death and begin to fear a possible repeat of the tragedy with the new craft.

Dorrington's apparent casual attitude toward procedure and safety provides ample reason to suspect that such could be the project's eventual conclusion.

But the enduring allure of flight, symbolized by the film's images of the forest's swift birds, and the strength of ambition fused with ingenuity and hope see the project through to its spectacular ending.